For the last fifty years Rolex have pursued one policy with an almost myopic vision; that of self-sufficiency. In that period, they have purchased bought almost all of the sub-contractors who used to supply them. Genex, who made cases were one of the first to be bought, then they bought Gay Freres, who made their bracelets and around a decade ago they bought Beyeler who were one of their major dial suppliers. These suppliers, and many more were scattered all around Geneva and throughout Switzerland, at one point Rolex had 27 factories; hardly the height of efficiency, so, starting in the 1990s they began a decade long programme of consolidation.

The 27 factories became three mega factories; dials were made at Chéne-Bourg, which is also where diamond and jewel setting takes place; Plan les Ouates is where both cases and bracelets are manufactured and where Rolex operates its own gold foundry; whilst Acacias is where final assembly and testing takes place. The Acacias plant is also the firm’s world HQ and where all of their research & development is carried out.

Rolex Chéne-Bourg

Rolex Plan les Ouates

Rolex Acacias

Yet despite all this consolidation, there was one part of the watch that Rolex didn’t make, and that was a rather important part, the movement. Although all the movements came from one factory which even bore the name Rolex, they didn’t own it, it was owned by the Aegler/Borer family; a family arguably as important as Wilsdorf in the history of Rolex. To understand the relationship we have to travel back over a century to the very founding of Rolex; actually, even further back, to the founding of Wilsdorf and Davis in 1905. In these early days, the firm didn’t make watches, rather it assembled them; buying movements from a few Swiss firms and putting these in cases bought from firms in the UK and in Switzerland. The vast majority of the watches they were selling were ladies’ watches, because (at this point) almost no men wore wristwatches.

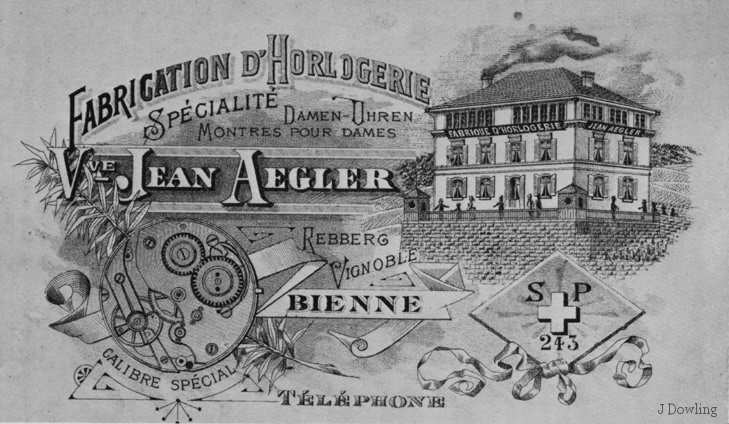

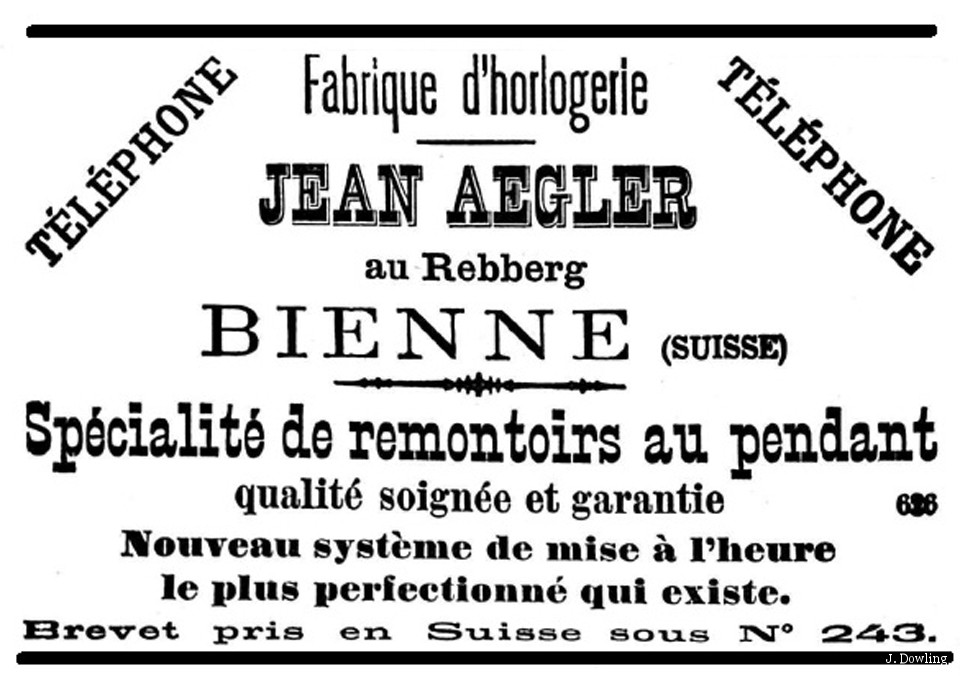

As the business progressed, Wilsdorf decided to return to Switzerland, where he had previously worked, to seek out a single movement supplier, rather than the several he had been using. His eye alighted on the firm of Jean Aegler in Bienne, as they specialised in movements for ladies’ watches, as this advertisement for the original company emphasises.

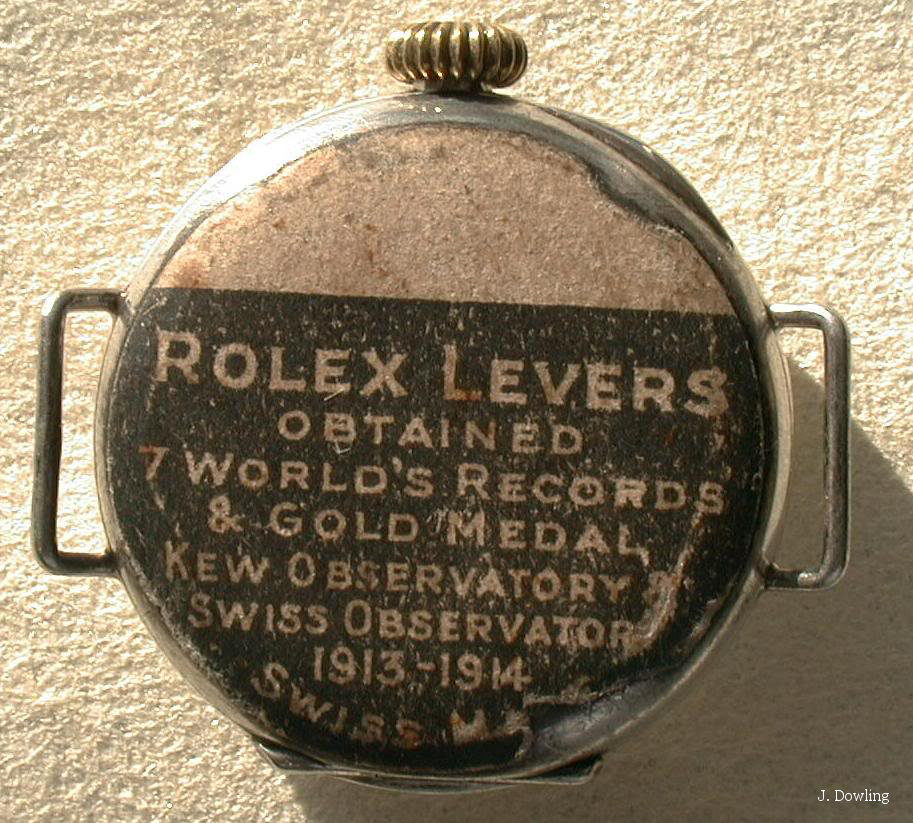

He developed a close relationship with Hermann Aegler (one of Jean Aegler’s sons) and subsequently gave him the largest order for small watch movements ever placed in Switzerland. What was special about Aegler was that they specialised in Lever Escapement movements at a time when almost all small movements had Cylinder Escapements, which are inherently less accurate. Look at the label on the back of this 1912 Rolex, powered by a Rebberg movement from Aegler, the word ‘Lever’ is as prominent as ‘Rolex’.

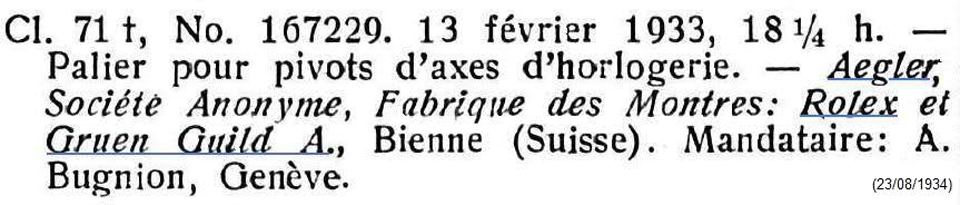

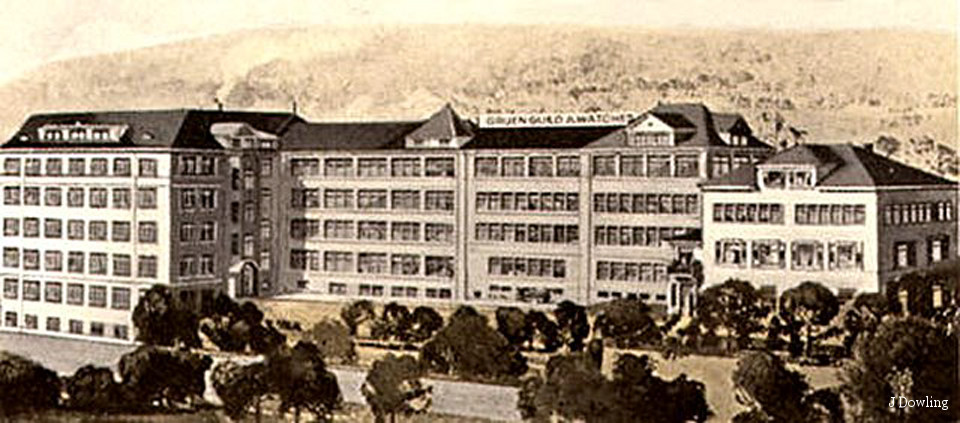

Over the next few years the relationship between Rolex and Aegler blossomed, each riding on the popularity of the wristwatch, in 1920 Hermann Aegler became one of the owners of Rolex when he purchased 6,960 shares and was appointed to the board, along with Wilsdorf and Davis. By now Rolex was Aegler’s largest client and their second largest was the US firm Gruen. In the late 1920s two important things happened, Hermann’s nephew Emile Borer became technical director at Aegler and the relationship between Aegler and its two most important clients became formalised for the first time. Both Rolex & Gruen purchased shares in Aegler, which was then renamed “Aegler, Society Anonyme, Manufacture des Montres: Rolex et Gruen Guild A” which means “Aegler Inc; makers of watches (actually movements) for Rolex & Gruen Guild A” (the Guild A watches were the highest grade watches that Gruen sold). For the first time Rolex owned a piece of its own movement manufacturing operation.

What was quite funny was that both Rolex and Gruen liked to imply that the factory, which was still majority owned by the Aegler/Borer family, was actually owned by each of the watch firms. Have a look at the image in Gruen’s advertising.

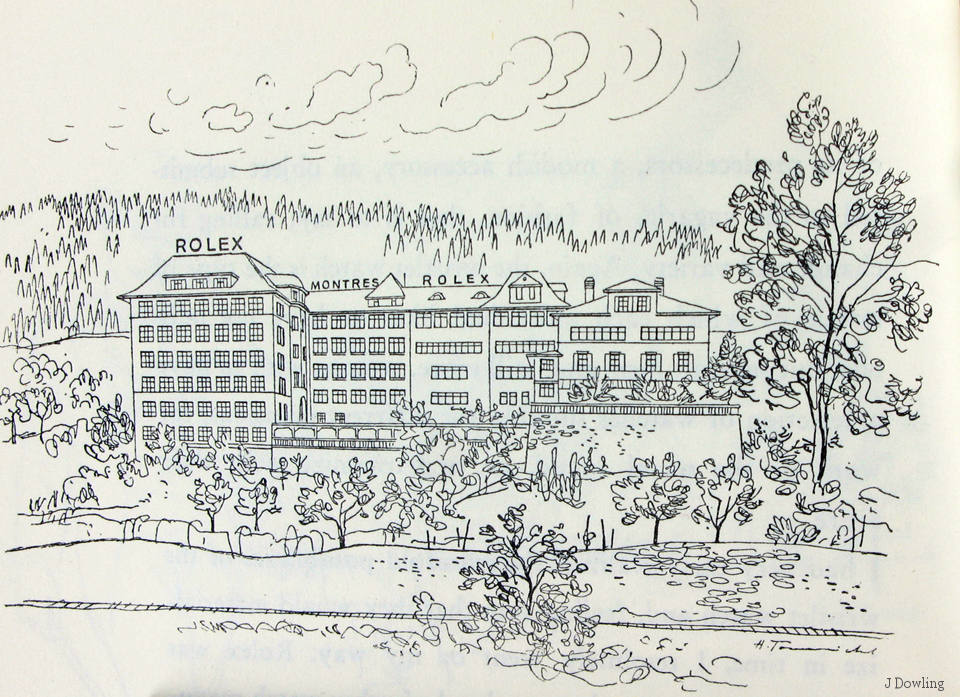

and at one from a similar period in a Rolex publication;

The interesting thing to note is that both these illustrations are actually drawings, because neither of them reflects the real signage on the factory.

Towards the end of the 1930s, Gruen sold their shares in Aegler back to the factory and at that time Rolex Geneva did the same thing; simultaneously with this, Aegler sold their Rolex shares back to Wilsdorf. This meant that the two factories now had single family ownership; Geneva with Wilsdorf and his wife, May and Bienne with the Aegler/Borer family. However, this did not reflect a worsening relationship between the two, rather it signified a new stage in the relationship; the Aegler factory was renamed “Manufactre des Montres Rolex SA” and the two families agreed that, from now on, Geneva would only use movements from Bienne and that Bienne would only sell movements to Geneva.

This convivial, yet completely informal, relationship lasted for almost seventy years, but in March 2004 an email landed in my in-box which amazed me; Rolex Geneva had bought Rolex Bienne outright; and, not long after, the consolidation masterplan was modified to include the Bienne facilities.

Over the years, the Bienne factory had been expanded to meet the increased production needs, but it was already becoming cramped; take a look at the image below.

The tallest building, in the centre with the word “Aegler” on the roof was the original Jean Aegler building and all the others were added on, over the years, sometimes this involved parts of the complex being on different sides of the road, connected by overhead bridges.

So, even prior to the acquisition, it was decided to move to a green field site on the outskirts of Bienne and the first stage of the move to the new facility at Champs-de-Boujean was made in 1993, with a subsequent move in 2003. In other words, Rolex Bienne was out of the old factories even before Rolex Geneva purchased them. But two years after the purchase, Rolex bought a 46,000 Sq M site adjacent to the Champs-de-Boujean site. For those of you unused to metric measurements, the new site is the equivalent of over six US Football fields and is connected to the existing site which is the same size; in other words the new Rolex Bienne facility is the size of 13 US Football fields.

Construction on the site began in the summer of 2009 and almost exactly three years later, the site was ready for the official opening. The delays between the purchase of the site and the start of construction were due to the decision to make the new factories in the mould of the Rolex Geneva ones, with high levels of energy efficiency and a very sophisticated parts storage and retrieval system.

I do half a dozen watch factory visits a year; and with almost all the major brands, there is one constant: none of them allow photography within the production areas. But this isn’t because they don’t want their competitors to know what is going on; rather it is because they don’t want us customers to know that the inside of one watch factory looks just like every other watch factory. A few Electro erosion machines and banks of CNC controlled multi axis drilling & boring machines. And there isn’t even much variety amongst the machines, as all of them come from a very small group of suppliers. Not at Rolex, who make so many watches that they are in the privileged position to design and commission much of their own production machinery. So, the Rolex factory doesn’t look like everyone else’s; for example, let’s talk about security; watches are small, portable and high value. So, many firms will lock away their watches, which are in the process of production, every night in a safe like this:

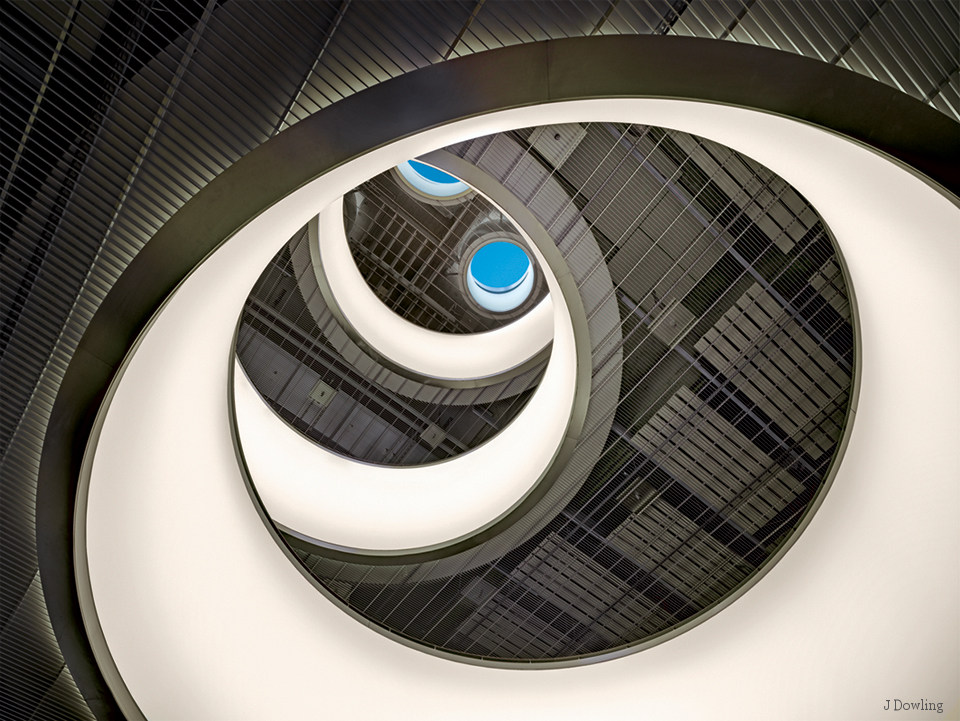

This is the Rolex equivalent at the new Bienne facility:

Three stories high, but all underground, the automated stocking system is a high-security vault, located on the underground floors of the new building.

Consisting of 14 aisles of shelves, each alround 30 feet high, it has a total of more than 46,000 storage compartments.

Each of these spaces is able to receive parts in various forms of packaging placed on transport trays. In total, the vault is able to store tens of millions of components. Each aisle is served by conveyor robots –14 in all – (one per aisle) which pick up from the shelves the required trays and automatically place them on the distribution conveyors which go to the various working areas. These conveyor robots move at 10 feet a second. The delivery takes place via this vast horizontal conveyor network, including four vertical distribution towers similar to elevators which are almost 90 feet tall. The system is so efficient that it takes barely a few minutes to deliver the tray to its destination.

On each floor, near the distribution tower, a delivery station allows the users to pick up the trays they have ordered from stock and to send back those that are to be returned for storage. In total, 22 stations are set up, two of which are double: one at the receiving docks and the other dedicated to the checking and washing of components delivered by suppliers.

Computers control the automated stocking system and all the flows. A routing system coordinates some 60 programmable controllers, which manage the tray movements under way and guide the trays between the stock area and the workshops. The whole installation is continuously overseen, 24 hours a day, by an extremely high-performance software program.

Because the whole operation is computer controlled and parts can be accessed at any part of the factory, there is no need for a human being ever to enter the space; so it is not only an automated storage and retrieval system but it is also a very high security vault, containing literally millions of parts, worth millions of Swiss Francs.

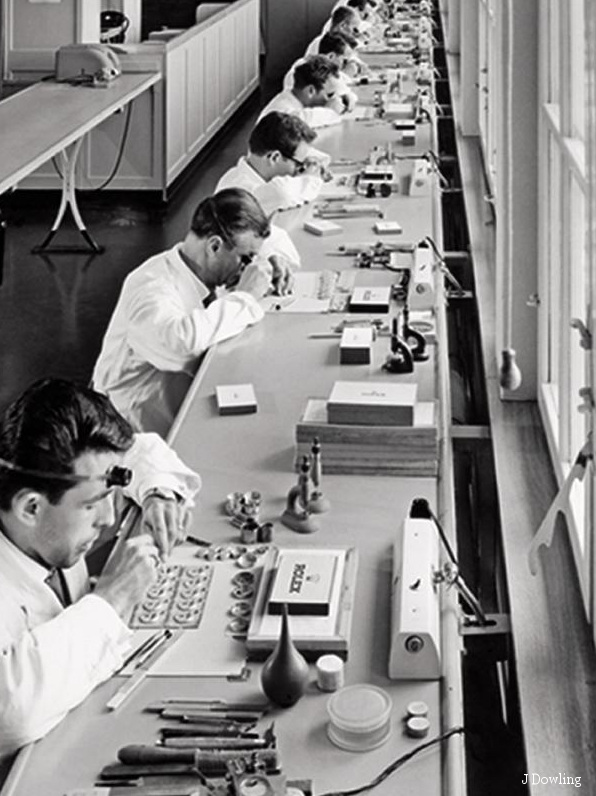

Earlier I talked about the machinery that Rolex use, what is important to understand is that this machinery is used to produce the parts, the assembly of those parts is still done by hand, the way it has always been done at Rolex.

Here are the assemblers at Rolex, hard at work in the 1950s:

And here they are in the new Bienne facility:

The most specialised workers at Bienne are the folks who produce the Parachrom hairspring; which is completely made at Bienne; right from alloying the special Rolex patented alloy, all the way to making the Breguet overcoil before it is attached to the balance wheel.

Here are some of those folks at work:

In the lower image you can see how the view from the windows is on to a forest, although the site is not far out of Bienne it is not only set in a green environment, it is a very ‘green’ building, following in the footsteps of the new Rolex Geneva factories.

Like them, there is a rooftop garden, where water used by the factory is used to water the plants, many of which are herbs used in the kitchens in the nearby rooftop restaurant. The plants and their soil also provide a very efficient thermal barrier for the buildings, preventing heat from escaping during the cold months and protecting the interior from the heat of the sun during the summer.

As well as having almost all glass walls, the interior of the building is also flooded with natural light by virtue of ‘light wells’ situated throughout the central area. Reaching from the roof to the ground floor; like lamps, these overlapping wells bring natural daylight to the centre of the common areas. Their layout is reminiscent of the gear trains of a watch, a spectacular visual reference to the movement. The materials used – glass, stainless steel, light and dark wood – give a very contemporary feel to the whole interior.

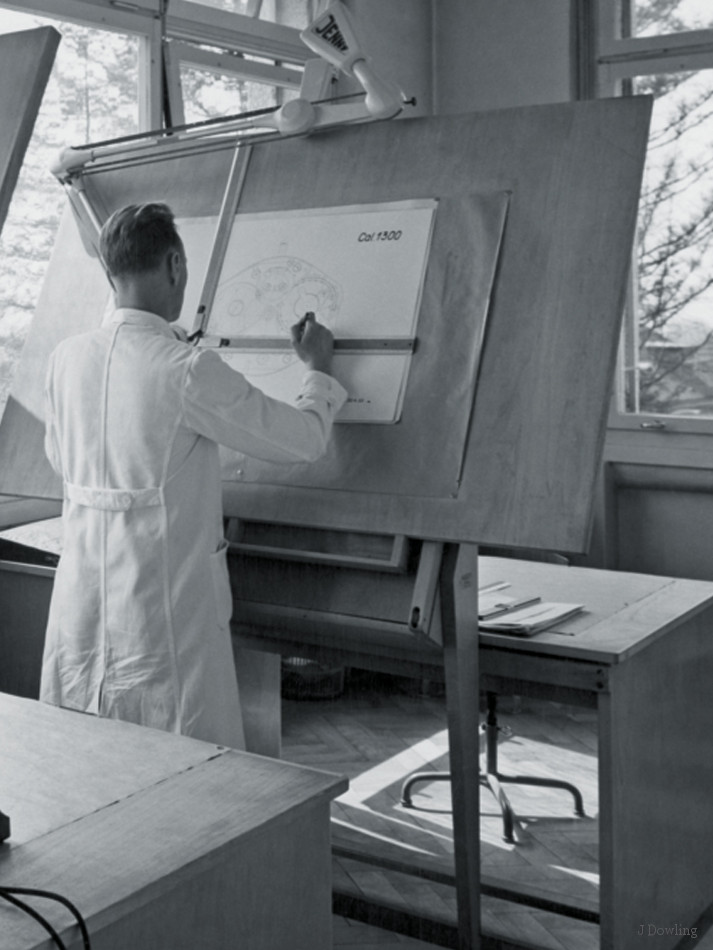

The reason for having so much natural light is that not only does it cut down on the need for artificial light and energy but it is so much better to work under, and it is for this reason that watch ateliers were always on the top floor of buildings and if we look at images of Bienne in the 1960s, we see that even then, as much work as possible was done in under natural light.

What seems amazing, if you think about it, is that this giant complex is devoted to the production of only four different movements; the Rolex 22XX series, as found in the ladies’ and mid size watches; the 31XX series found in the gents’ watches; the 41XX Daytona movement, also used in the YM II and the new 90XX calibre used, so far, only in the new Sky Dweller. However, when you realise that they don’t just make the movement blanks and bridges here, but they even make the jewels, the shock protection and even the lubricants used in the watch right here in Bienne, you realise just how monumental the operation needs to be.

Bienne currently employs around 2,000 people, around a third of the firm’s total Swiss staff, with the rest at the three Geneva factories and head office. These new facilities are designed so that they can be doubled in size should the need arise; meaning that after more than a century on one site in Bienne, Rolex are set for their second century in the town in their new complex.