Cartier

100 not out: the full history of the Cartier Tank

As the Cartier Tank passes its first centenary, we take a look back at the dynamic – and surprising – history of one of the world’s most recognisable watches

As the Cartier Tank passes its first centenary, we take a look back at the dynamic – and surprising – history of one of the world’s most recognisable watches

The Cartier Tank is one of the most recognisable watch designs ever made, but what most people do not know is that it is also one of the rarest. In the 50 years since it was introduced on November 25th 1919, until the end of December 1969, less than 6,000 Tanks were ever made and sold by

.

The early years

It is now axiomatic that the design of the watch was influenced by the plan (or top) view of the first Tanks, which were rhomboid shaped with their tracks running all around the body. Much less known is that the development of tanks in WW1 was mostly done by the Royal Navy, after the British Army’s War Office initially turned them down. But the RN proceeded with the idea, under the leadership of Winston Churchill who saw how these new ‘Landships’ had the potential to challenge the stalemate of the trench warfare in WW1.

However it was decided that calling them ‘Landships’ would make the purpose of the new machines obvious to the hordes of German spies who were assumed to be crawling all over Britain. So the more ambiguous name of Tank was chosen.

While the silhouette of the Landship may have influenced Louis Cartier, the truth is that as a jeweller he was an artistic soul, living in Paris and the war was not the only thing happening at that time; this was the dawning of Cubism in art, of the Bauhaus movement in Germany and the influential de Stjile magazine in Holland. Simple, machine-influenced shapes were becoming all the rage and Louis Cartier couldn’t help but be aware of them.

Despite the fact that it was a very simple and pure design, it still followed the design codes established earlier with Cartier’s first wrist watches; a “railway” style minute track, radiating Roman numerals, blued steel Breguet hands, deployant buckle (a Cartier invention) and the one piece of decoration on the entire watch, a cabochon-cut sapphire surmounting the minutely knurled winding crown.

In reality the watch was the product of two designers; we have discussed Louis Cartier, whose name was on the dial, but equally important was Alsace-born Edmond Jaeger. Jaeger had designed movements for many of the great watchmaking firms, but his closest relationship would be with Cartier. Together they formed a business called European Watch & Clock; the movements that Jaeger designed were then made by the Swiss firm of LeCoultre. The new firm was founded shortly after the launch of the first Tank watches on November 15th 1919, meaning that for the first few months of production, the LeCoultre movements inside these Tanks went unsigned.

The first production run of these radical new watches (if we can call it that, as each watch was completely handmade) reached the shops at the very end of 1919, and the run was very short. Only 6 watches were made, but they all sold within a couple of months. So 1920 saw the production ramp up to a dizzying 33, which was close to the annual average for the early 1920s, but the production in the second half of the decade averaged 104 watches per annum. Then came the Wall Street Crash and in the next five years they sold 102 total; it would be 1960 before they made more than 100 watches in a year again. Things got so bad for Cartier that in 1933 the LeCoultre contract with Cartier was cancelled by the Swiss firm as Cartier was not keeping its side of the deal by ordering sufficient movements.

Attempts to increase sales by introducing variations on the Tank theme were only mildly successful, but they produced some of the most interesting versions of the Tank; starting with the Tank Cintrée (“curved” in French) which took the format of the Tank and extended it lengthways whilst also curving it to fit the wrist.

Next came the Tank LC, which was a compromise between the first Tank, which was square, and the Cintrée, in that the dial and case were stretched to become rectangular but not as long as the Cintrée and not curved. This new model is now the shape we associate with the words “Cartier Tank”.

Next came the Tank Chinoise, which reverted back to the original square shape of the first Tank (now called the Tank Normale) but bulked up the case dimensions by adding horizontal bars above and below the dial, notionally inspired by the roofs of Chinese temples. It not only made the watch more in-keeping with the oriental themes prevalent in fashion & interior decoration but also made the watch much more masculine looking, despite the small size.

Even more bizarre experiments followed, including the Tank à Guichets, which took the case of the Tank LC but obscured the dial with a sheet of brushed gold, with two small windows (Guichets in French), the upper one showing the hour which jumped as the minutes, shown in the sector opening below, reached 60. It was a perfect watch for the machine age, but it was difficult to tell the time with and was another commercial failure.

Then, along came WWII, the Germans occupied Paris and the HQ was cut off from its two Anglo Saxon branches, London & New York City, with their more affluent clients. That was just the beginning of the tragedies about to engulf the house of Cartier, as both Jacques and Louis Cartier died in 1942; the remaining brother, Pierre, who had been running the NYC operation returned to Paris and oversaw the restructuring of the firm after the war, but the austerity imposed in France decimated their customer base and soon both the New York and London companies were sold off to investors. It was not until the 1960s that Cartier began to regain its allure; but then Pierre died in 1964 and now the last of the three icons was gone.

Refuelling the Tank

Two men are responsible for the revival of Cartier, but not the ones that everyone talks about; they are the two Bobs, Robert Hocq & Robert Kenmore. Kenmore was chairman of the Kenton Corporation who had bought Cartier NYC and believed that the retail industry was fragmenting into inexpensive high volume shops and high end ones. His firm owned Mark Cross, Georg Jensen, The House of Valentino and several fur companies as well as Cartier Inc and lower priced department stores called Family Bargain Centres.

He wanted to provide synergy between his disparate brands and initially opened a branch of one of his fur coat operations inside Cartier’s Fifth Avenue store. I don’t know how successful this was, but his next idea really took off. He began to make gold-plated versions of the Tank and sold them through his department stores and others in North and South America.

At around the same time; Robert Hocq was running a cigarette lighter firm called Silver Match in France; they sold inexpensive butane gas lighters, not quite disposable, but very low priced. He knew that he could never compete with the luxury lighter firms, such as DuPont or Dunhill, but he believed that there was a gap in the market for a stylish lighter priced above his but below the two “D” brands.

He was smart enough to know what he wasn’t good at and so hired a designer to come up with an extremely good looking product; the new lighter was based on the design of a Greek column, with a fluted body and a band running around the top. He knew that the name of his brand didn’t have enough clout and so looked around for someone who would licence their name to him; his first choice Van Cleef & Arpels turned him down and so he next approached Cartier who were happy to give him a licence.

The rest, as they say, is history; the Cartier lighter became the must-have accessory at the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s. The Rembrandt group of South Africa (run by Anton Rupert) had grouped their external operations under the name of Rothman’s International; they were the next people to obtain a licence from Cartier and began to sell Cartier-branded cigarettes shortly after. Both these gentlemen saw that the potential was there and made an offer to buy Cartier Paris from the current owners.

The deal went through in 1972 and Hocq installed his sales manager, Alain Dominique Perrin, the guy who had made the Cartier lighter such a success, to run Cartier. Perrin had seen the success of the gold-plated Tanks sold by Cartier Inc and was determined to replicate that success. In 1973, the first items in the new Must de Cartier range were introduced: sunglasses, scarves and (of course) new variations on the lighter.

These products were all produced by outside suppliers who licensed the name from Cartier; it took until 1976 to launch the first of the in-house Must line, the Must de Cartier Tank. Unlike the US entry-level watches which were gold-plated base metal, the Paris versions were made from Vermeil, which in English is known by the much less exotic name of Silver Gilt, and is gold-plated sterling silver. This gave these new watches the cachet of being made from a precious metal whilst still being affordable, while the larger versions offered both quartz and hand wound mechanical movements.

Perrin took a leaf from the playbook of Nicholas Hayek and his phenomenally popular Swatch watch and released endless versions of the Tank Must de Cartier for men and women, in a multitude of sizes, dial colours and finishes.

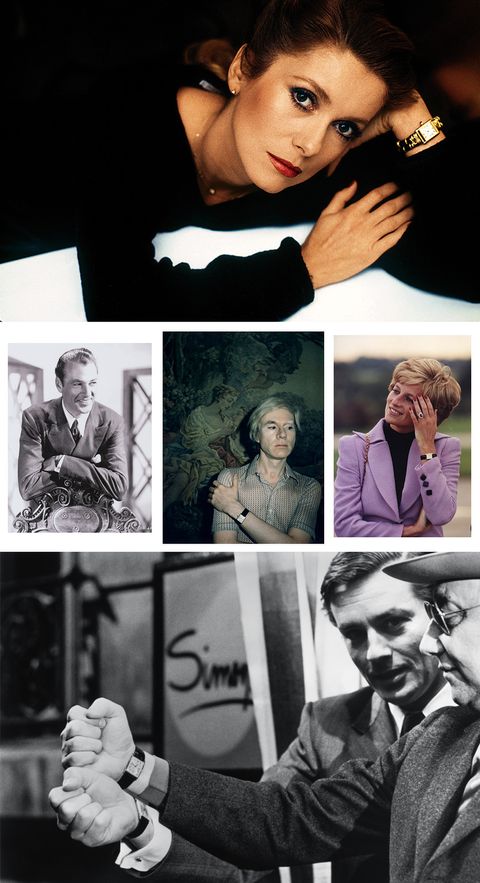

In 1973 Cartier relaunched the Tank with ultra flat, Tank LC and Tank Normale versions now available as regular production pieces. And riding on the popularity of the Must de Cartier range, the Tank LC was soon seen on the wrists of everyone from Jackie Kennedy to Andy Warhol.

The Must range provided the investors with sufficient funds to buy both the New York and London operations and slowly but surely Cartier quietly cancelled all the licences for sunglasses, scarves, perfume etc and brought everything in house.

The last licence issued was to the Ford Motor Company, and from 1976, for seven years, the most ostentatious model of the already flamboyant Lincoln Continental Mk IV bore the name “Cartier Edition”.

The Richemont Era

After Robert Hocq died in 1979, struck down by a car in the Place Vendome, the Rupert family steadily increased their holdings in Cartier until by 1998 they owned all the shares and Cartier became the flagship of the new Richemont. Under the leadership of Perrin and then Bernard Fornas, new versions of the Tank were introduced; starting with the Tank Americaine in 1989 (really an updating of the early Tank Cintrée), then came the Tank Française in 1996, whilst in 2002 along came the Tank Divan, an extra wide version and in 2012 came the last of the ‘Allies’ Tank watches, the Tank Anglaise.

The majority of these watches are now made in Cartier’s vast new factory in the Vallee de Joux, but in 1998 Cartier opened a small workshop atop their Place Vendome flagship store and in it built by hand small collections of their iconic watches. Called Collection Privée Cartier Paris, they brought fine watchmaking back to the centre of Paris, only a few hundred metres from where the first Tank had been built on the Rue de la Paix. It was therefore obvious that the first watch to be launched in the new Collection Privée Cartier Paris should be a Tank.

Those Must de Cartier watches finally faded from the catalogues of Cartier around the turn of this century and now the name lingers on only as a perfume, interestingly in a bottle that mimics the shape of the Cartier cigarette lighter that Messrs Hocq and Perrin used as the first step in the revival of one of watchmaking’s great names.