This is a really tough report to write for a number of reasons; firstly it involves me saying that I am wrong, and as a guy, that isn’t something I relish. Also there is (as they say) ‘history’ between us (Montblanc, Minerva & me).

Let me try to explain; let’s be honest, Montblanc has never really been taken seriously as a watch company, they make nice pens, particularly the limited edition ‘Writers Series’ (full disclosure, I own a few of those pens & use one of the Alexandre Dumas pens to sign letters), but as to watches, they were pretty much ‘Johnny Come Lately’ and had little to attract the true watchnut. I always believed that the SIHH held a similar opinion, as the Montblanc presentation was always the last one on the last day for the press, usually many of the press would leave early and miss it, whilst others would show up only out of duty. In fact, I remember one Montblanc presentation where a watch writer fell asleep & started snoring during the PowerPoint presentation.

Then a couple of years ago it was announced that Richemont had bought Minerva watches, not just the brand but also the factory & shortly after it was announced that the Minerva brand was being ‘given’ to Montblanc. To those of us who had followed & cherished Minerva, it was as if a five year old had been given command of a Boeing 747. Those with long memories on Timezone will remember the close relationship between TZ & the Frey family who had owned Minerva. Around a decade ago the Freys made two limited edition watches for TZ, I think they were the first LE ever for us. They were based on their Pythagore watch dating from the dark days of WWII & a beautifully simple, classic time only watch. Both editions sold out & I still have mine, a black dial one with rose gold batons & hands. When the Freys sold out in 2000 to Emilio Gnutti, an Italian businessman with a somewhat checkered recent history, many of the TZ Minerva fans felt that the brand had lost its soul, particularly as the new management wanted to take it much more upmarket. In order to accomplish this move upmarket they hired one of the most accomplished watchmakers of modern times, Demetrio Cabiddu, who had worked with Genta on the design of the minute repeater sonnerie and subsequently at Minerva’s neighbour, Blancpain.

The decision to take the brand upmarket meant that the new management immediately increased the prices of the current models by a factor of two or three. To say that there was resistance on the internet watch forums where Minerva had found its new customer base would be putting it lightly, essentially there was a revolt & people looked on the new management as though they were the four horsemen of the apocalypse. It came to a head when I approached the Minerva stand at the Basle fair of 2002 on the Press Day, for the first time in my life (and so far only) I was thrown out of a stand; vituperation, in a heady, emotional mix of English & Italian was hurled at me as I scampered away; fully aware of how the world had now changed, at least as far as Minerva and Timezone was concerned.

Before long Mr. Gnutti had rather more important things to worry about than Minerva, he was Chairman, President, CEO or on the board of many companies in Italy including the recently privatized national telephone company & subsequently was caught up in the scandals surrounding the privatization of much of Italy’s infrastructure. At one point he was sentenced to six months in Jail, although via many appeals it is uncertain whether or not he has actually served any time behind bars. Nevertheless it must have been a relief to him when the deal was done with Richemont & the factory was no longer part of his portfolio.

Then last year, a couple of months before the SIHH, I got an email from Montblanc’s PR folks asking if I was interested in a one to one meeting with anyone at the SIHH. Only being polite I asked if they might have anyone from the Minerva operation who would be available & the reply came asking if I wanted to meet with the head of the operation, Hamdi Chatti. Suddenly my attitude changed, I have been around the watch business a little too long to have idols; but there are a number of people I truly respect & Hamdi is one of them. I first met him when he was running the Fine Watchmaking division of Harry Winston, where his responsibilities encompassed the Opus line of watches as well as absolutely amazing tourbillons & perpetual calendars.

However, before my meeting with Hamdi, there was another regular Montblanc presentation that I had to endure (or so I thought); for the second year in a row we were shown the Nicolas Rieussec single pusher chronograph, and last year I did little more than acknowledge its existence, this year I looked a little more closely and found much to admire. Students of language will know that the word ‘chronograph’ means ‘time writer’ and that is what the very first chronographs did, by virtue of a revolving dial below a stationary pen. Nicolas Rieussec invented this very first chronograph in 1822 and Montbanc (who, as we all know, have a history in writing equipment) chose to copy the layout of this writing chronograph rather than follow the more conventional design route.

The design of the chronograph features two small dials at the 4 and the 8 positions with fixed blued steel hands standing vertically above them. When the chronograph is operated the dial discs revolve and you read the elapsed time by the fixed hands. It isn’t just that they have chosen an unusual operating system that makes the watch stand out, the movement which powers it (the first from Montblanc’s own factory) is stunningly designed & finished.

I really like the design of the movement, with its balance assembly at the bottom of the movement, placed perfectly in the centre, the diagonal Cotes de Geneve are a nice touch and the symmetrical layout of the jewels on the chronograph bridge shows that there has been significant thoughts about the aesthetics of the movement itself.

So, by the time of my meeting with Hamdi Chatti I was feeling rather more favourably disposed towards Montblanc than I would ever, previously, have thought. When I arrived for my appointment Hamdi was still involved in a meeting, so I took the opportunity to wander around the stand and look at the stuff on display. On a table was a display of enamel dials in various stages of completion and next to them were a series of dial drawings & case drawings. A member of staff came up & explained to me that these were part of the new custom watch operation. A client can approach the factory, where they will work together with a designer, they will agree on the type of movement to be used, the layout of the dial, which material it will be made from, fired enamel, silver or brass, and whether it will be guilloche or not and if so, in how many patterns. The design of the case can be chosen, as well as the material and all of these choices are drawn on separate sheets of translucent paper and overlaid on each other until the client arrives at a combination they want and only then does manufacture begin. It is an interesting idea, halfway between having a watch completely custom made by someone like George Daniels and buying a regular limited production piece. It is obviously never going to be a major business, but it goes a long way towards establishing Montblanc/Villeret as different from the herd.

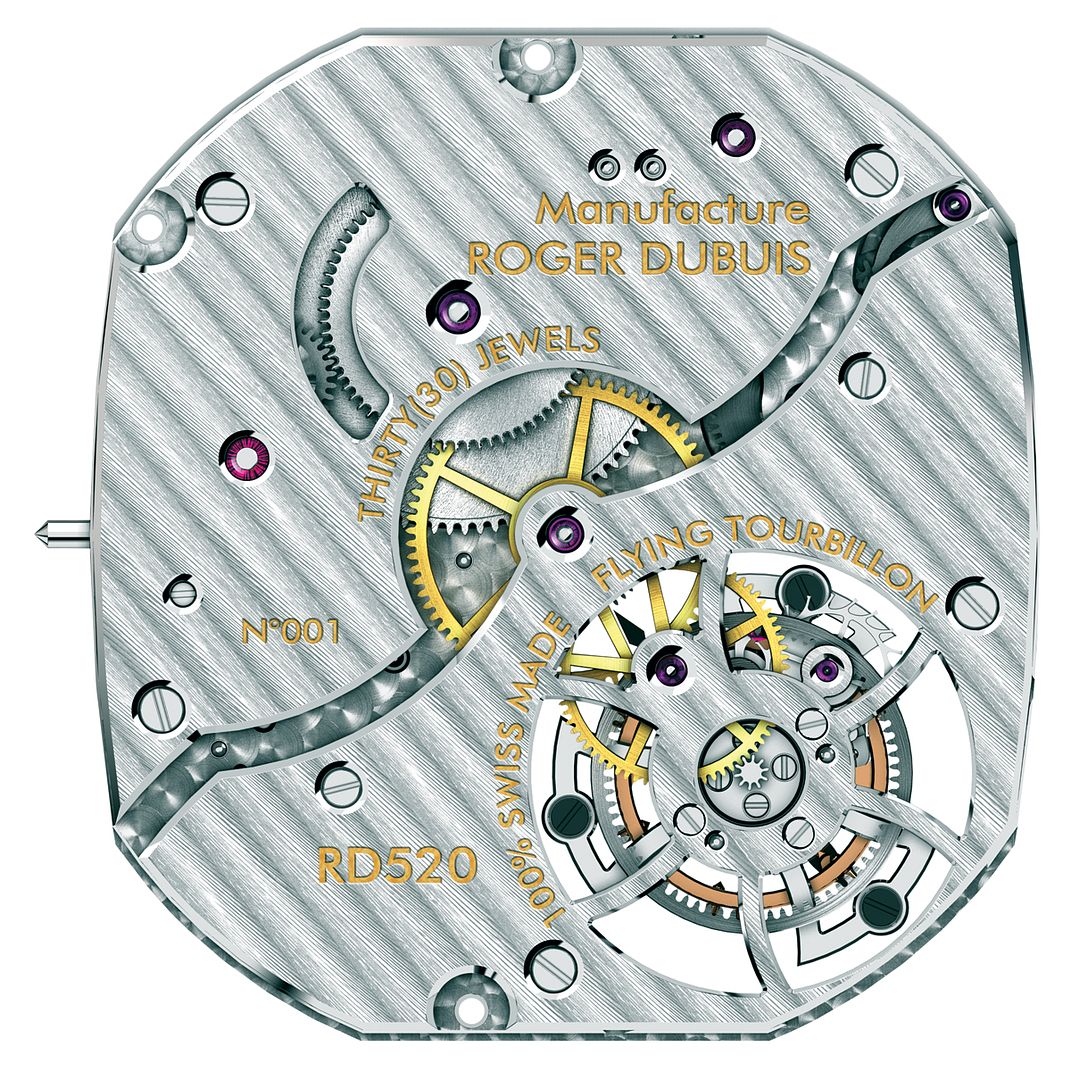

Looking further around the stand, I saw a display of movements and took the chance to examine them under my loupe, I was seriously impressed. It wasn’t just the finishing, it was the layout & the overall appearance that grabbed me.

They look as if they could have been made at any time from the turn of the last century to the 1970s, but certainly not in the 21st century. Look at that huge balance wheel, look at the beautiful curves of all the bridges & levers, gaze with reverence upon the sawn’s neck regulator lever & look at the humour inherent in the use of the Minerva trademark ‘arrow’ at the end of the blocking lever; Minerva being the goddess of both the useful & the ornamental arts and this movement most certainly qualifies for both categories.

This movement has been designed by someone with sensibility & feeling, as well as a thorough understanding of movement design. And when I saw the watch into which this movement is fitted, I also knew that whoever was in charge of watch design was equally talented.

Like every other Montblanc/Villeret watch I saw, the dial was stunning, a perfect 4 piece black fired enamel one with a depth that almost invited you to dive in.

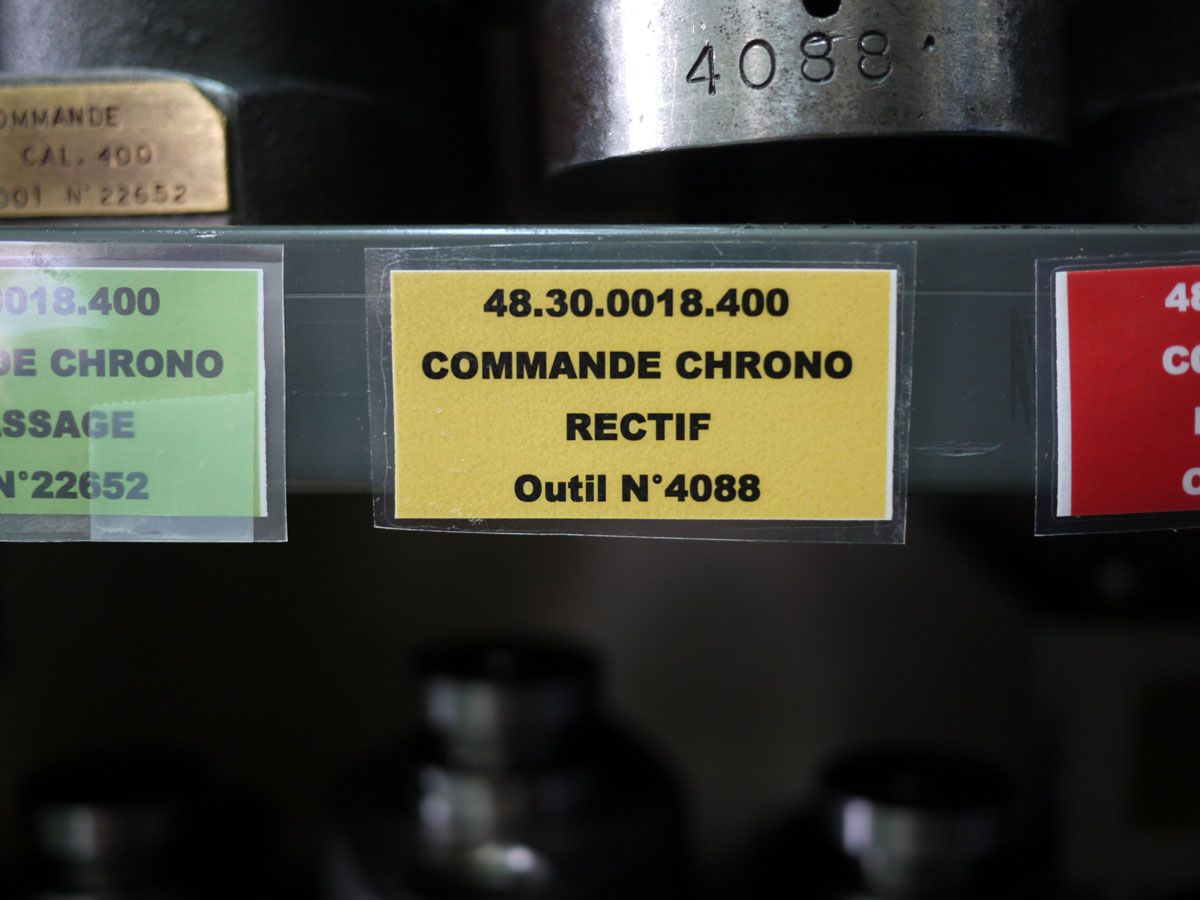

By this time Hamdi was through with his meeting & I was able to renew my acquaintance with him, after the usual pleasantries we began to talk about how the Montblanc/Minerva/Villeret operation will continue. He explained to me how lucky they were when they bought Minerva, as it was almost a ‘time capsule’ of old style watchmaking. Although the Gnutti team had introduced new wire erosion machines & CAD/CAM systems, they had not got rid of the old machinery and tools. Also, because Minerva was so small and their specialization in sports timers & chronographs so tightly focused, they were not hit by the ‘quartz revolution’ nor by outrageous case designs; two maladies which decimated the rest of the Swiss watch industry during the 1970s and 1980s.

Demetrio Cabiddu and his young team have all stayed on after the Montblanc takeover and now a tightly focused program is well underway at the factory. Development of an automatic movement has been abandoned and all Montblanc/Villeret movements will be hand wound. Also, almost all the watch movement is made in house, because they choose to make their watches the old fashioned way with big balance wheels & 18,000 bph, they even have to make their own hairsprings and balance wheels. All the finishing work is done by hand with every completed part personally inspected by M. Cabiddu after finishing & before it is assembled. Obviously this limits the production, but the decision has been made at management level to pursue the goal of the highest possible quality rather than that of quantity.

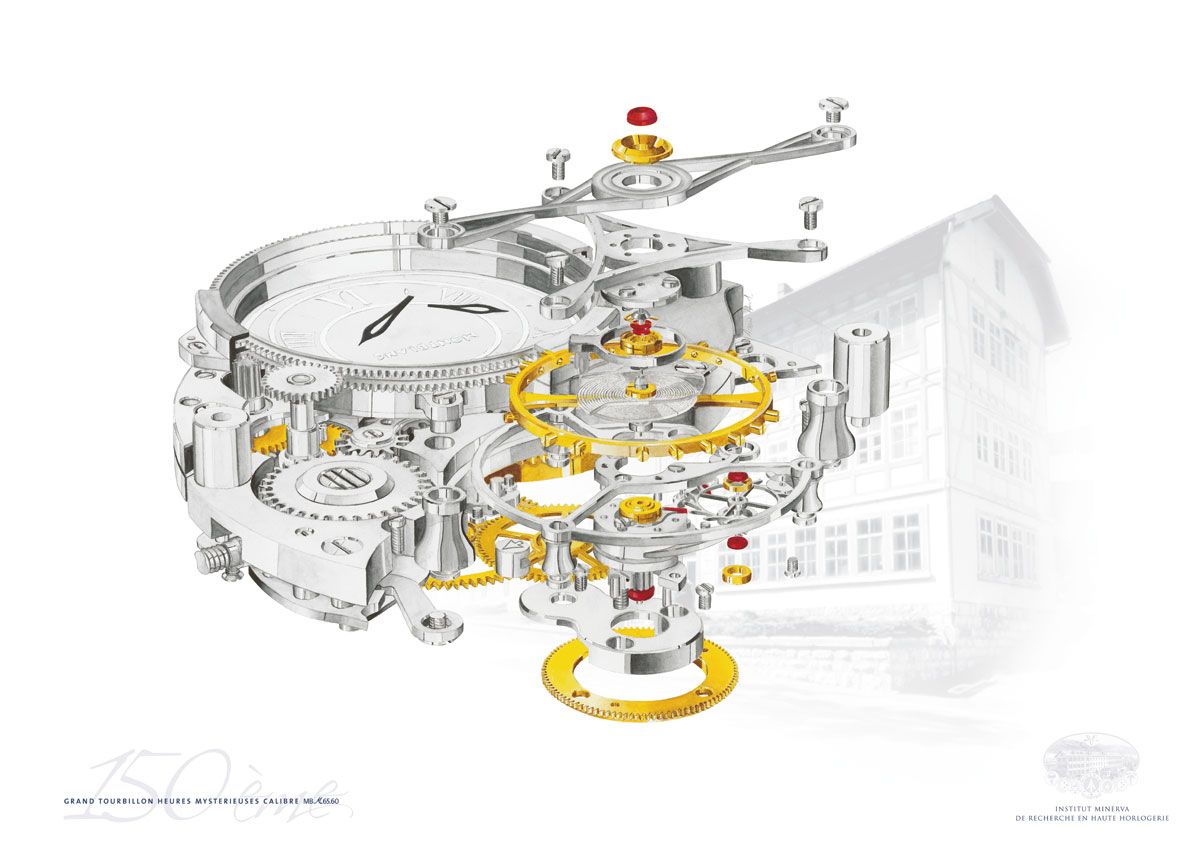

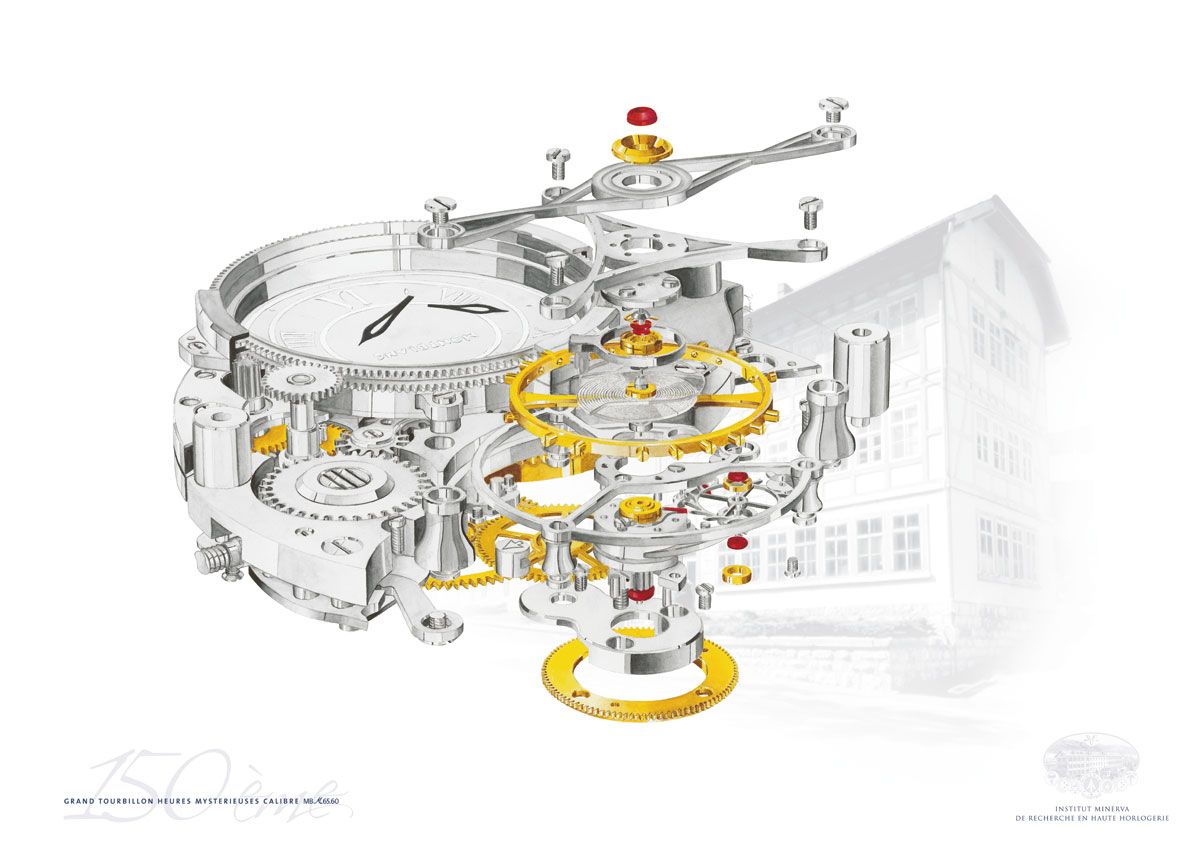

The design of most of the current production was well under way when Montblanc took over, and it was considered ridiculous to scrap all the research and development which had been expended, so although they were developed under the previous management, it is important to realize that they were developed by the same watchmaking team who are now building them. As well as the chronographs with which Minerva made their name & which are now being made with the newly redesigned movements, Montblanc/Villeret have introduced as their flagship a watch which the old Minerva could never have thought of; a tourbillon. Let’s be honest, making a tourbillon nowadays is nothing special, if you are a watch company & you want to have one in your product line, there are number of companies happy to supply you with the entire tourbillon system, ready for you to drop into your movement, or even to build the entire movement for you. This path is not the one chosen by Montblanc/Villeret, rather they have decided to make the whole thing in house; just take a look at the top bridge of the tourbillon.

Inspired by the mathematical symbol for infinity, this bridge looks like two fine wires pulled into an elongated figure ‘8’; but it isn’t, in fact this bridge is made from a single piece of steel, initially machined into a rough facsimile and then painstakingly finished by hand. With a tourbillon this unique, you wouldn’t expect the watch to revert to convention with its time display, and it doesn’t disappoint. It may be one of the first wristwatches to use the mystery display, first introduced by Cartier in their

pendule mysterieuse of 1913, where the hour and minute hands are replaced by two crystal discs with the outline of a hand printed on each one. The hands seem to float in space with no central post; whereas, in fact each disc is driven independently by gears on its outer rim.

The rest of the case top (I can’t really describe it as the dial) has some of the most stunning guilloche work I have ever seen, all of it hand done; it is much better than the work I have seen on recent Breguet watches and almost as good as the work on Urban Jurgensen or George Daniels. The case is a fitting housing for masterpiece contained within, almost heart shaped with the time dial extending the shape of the case below the expected circumference. It is a big watch, there is no doubt about that, but the design makes it look harmonious with the double stepped curved lugs flowing gracefully into the case with its domed bezel. Look closely at how the strap fits into the curve of the case bottom; I have rarely seen such precise meshing of two such disparate elements.

But the Mystery Tourbillon wasn’t the only special watch coming from Villeret this year & the next watch that Hamdi showed me was equally surprising, the Grand Chronographe Regulateur.

What appears to be a simple monopusher chronograph has a couple of surprises up its sleeve (if you will forgive the pun); the pusher at 10 operates a second hour hand which is usually hidden behind the regular hour hand. This system (similar to the one Louis Cottier patented for Patek Philippe in 1959) is one of the most convenient there is, giving an uncluttered dial in normal use and quick reading of the second Timezone when needed. Obviously because both hour hands revolve around a 12 hour dial, a day/night indicator is needed for the ‘home time’ and the watch has a tiny one near the 1 index.

As I mentioned earlier, all Montblanc/Villeret watches are manual wind only, so a power indicator is a good idea and not only does this watch have one, but it is one of the most interesting ones I have yet encountered. In the same way that most cars have a fuel gauge which slowly recedes as the contents of the tank decline & then, when you are down to the last 10% or so, a light will illuminate on the dash to reinforce the idea that it might be a good idea to find a filling station, the watch has a ‘Reserve Gauge’. This comes into operation when the watch gets down to just 12 hours power remaining, the silver power reserve hand stops at the 12 hour mark and a red hand comes out from behind it, slowly traversing the red reserve sector.

Once again the dial is a masterpiece, it is gold with multiple decentered Guilloche decoration, I love the little dramatic touches of red as accents on the quarter hour markers.

At 47mm, it is a nice sized piece; and, like all of Montblanc/Minerva watches has their patented hidden cuvette, which can be opened to reveal the sapphire back and the stunning movement.

These watches are handmade in tiny quantities, for example the last two watches I have discussed are made in a series of 8 each in both pink and white gold and a unique piece for each model in platinum. Distribution will be similarly limited, there are only 3 dealers in the whole of the US and just 2 in the UK. The plans are that there will never be more than 30 dealers worldwide.

After the Frey family sold the company in 2000, the new owners discussed their plans for the brand and stated that they wished to be talked about in the same breath as Patek Philippe & A Lange when high end horology was discussed. Along with the rest of the watch world, I laughed at the presumptuousness of the statement; now having looked at the watches coming out of the factory, I have to put my hand on my heart and admit “I was wrong”. These watches are easily the quality of the other two brands; the problem, as I see it, is that getting the quality to this level was an easy task compared to convincing the buyers that they have.

I wish them luck.