The watch industry likes to tell stories about the history and romance behind their brands, and we all buy into them, well most of us do but the rest of us know that the vast majority of the Swiss watch brands are all owned by one of three huge conglomerates and that there is as much romance about their history as there is about the sausage industry. But every now and then, you realise that there are some great stories in the business & when you come across one, you know that it is worth telling over & over again. The story of Charles Vermot and the Zenith El Primero movement is one of those, I have told the story before, but this retelling comes with some additional new information.

The tale goes back to 1975 when the US firm, Zenith Radio Corporation, owned Zenith; the quartz revolution was at its height and mechanical watches were in the doldrums. The owners decided that mechanical watches had had their day & the future belonged to electronic watches. Thus, an order came down from the US HQ to dispose of all the tooling for the movements & to sell the tools as scrap. Despite protests from management & watchmakers, the decision was irrevocable and furthermore the Swiss staff was ordered to dispose of the plans & blueprints, as these would also be of no use in the brave new electronic world.

However Zenith has a tradition and a history, people stay there for a long time; several of their current employees have been with the firm for over a half-century. This comes about through one thing; loyalty and it was this loyalty to the firm & its history & tradition that saved the El Primero. Charles Vermot was a senior watchmaker with the company & was entrusted with the disagreeable task of disposing of the El Primero tooling. Rather than follow orders, he meticulously wrapped each item, labelled it & took it to a disused area of the factory where the tools were arranged on shelves in the attic. And, in a notebook he copied down the exact procedures necessary for making the movement from scratch using the tooling he had saved.

And, it was in the attic that the history of the El Primero might have stayed if it hadn’t been for another small company in the neighbouring town of La Chaux de Fonds, who asked if Zenith might have some El Primero movements for sale. The resulting watch, the Ebel 1911 chronograph launched in 1982 proved to be a huge success for both firms, and so the tooling was recovered, put into use and before long Swiss watch companies were beating a path to Zenith’s door clamouring to use the only high quality automatic chronograph movement then available. The El Primero is a remarkably efficient movement, bearing in mind its 40-year-old design; it runs for 50 hours at full wind but if the chronograph is running, that autonomy is only reduced by 5 hours. However it is important to realize that the El Primero was designed in the 1960s when craftsmanship was at its height and it was not designed for large-scale industrial production, unlike (for example) the Valjoux 7750.

In fact during its 41-year history (including the enforced exile in Charles Vermot’s attic) the total of all El Primero movements ever made (including the hundreds of thousands found in the Rolex Daytona 16520) add up to only 600,000, by contrast over 1,000,000 Valjoux 7750 movements are made each year.

That is the story as it has been told here and elsewhere, here we go with the new stuff;

The original Zenith factory expanded over the years, winding its way down the hill on which it is built, the original part is a listed building which is not allowed to be externally altered in any way. There are plans underway to completely refurbish it internally very soon, but in its current configuration it is completely unsuitable for modern watch making and so has been almost completely abandoned. The watchmaking is currently carried out in the various buildings which have been added on to the original structure, this means that the different operations are spread out & so extremely inefficient, which is why the plan is to refurbish the old building then move all of the production there.

I was at Zenith recently to look at their Basel introductions and to spend some time with their CEO Jean-Frédéric Dufour who had recently been voted 'Man of the Year' by the world’s horological press, but after the meeting was over I accompanied Claire Ferrier out of the office building and up the stairs to the watchmaking area. After my visit she opened another door & we found ourselves outside staring up at the edifice of the original building.

She took an old key and opened a door which seemed to be made of old weathered fibreboard & beckoned inside; this was the view that greeted us:

This was the old control room where lubricating oils were sent throughout the building to each of the different departments, the floor was covered in dust and debris and cobwebs stretched across most of the fixtures, it was like walking into a time capsule of the Victorian age. From here we walked outside to another door, entered and found ourselves staring at a huge stone staircase, we slowly climbed it, gazing at the heavy chain hanging down the centre of the stair well.

At the very top of the stairs our passage was barred by a slatted wooden door, through it I could see some shadowy shapes.

Claire produced another old key and, with some difficulty, opened the door, turned on the light and invited me inside, this was the sight that greeted me as the first journalist ever to walk into the attic where Charles Vermot saved the firm's tooling.

Swiss watchmaking companies like to give the impression that they are all about precision engineering, micron tolerances and anal cleanliness; and, to be honest, that is how most watch factories operate, but this room was at the other end of the scale to those factories. It was dark, dusty and items were spread out all over the floor, stacked on chairs and on top of any other possible flat surface.

Not everything was in disarray, lots of items were on shelves, some neatly labelled and some not.

Lying in disarray on the shelves were the tools needed to make the individual calibres:

Including one of their most iconic calibres, the 135, winner of countless chronometer competitions from the 1950s until the competitions were finally abandoned in the 1970s.

Some of the wooden shelves were bowing under the weight of the tooling & I feared for the safety of the tools on the lower shelves.

Despite the fact that stuff was spread out all over the attic, covering any possible surface, there was one area which was clean & empty, this one;

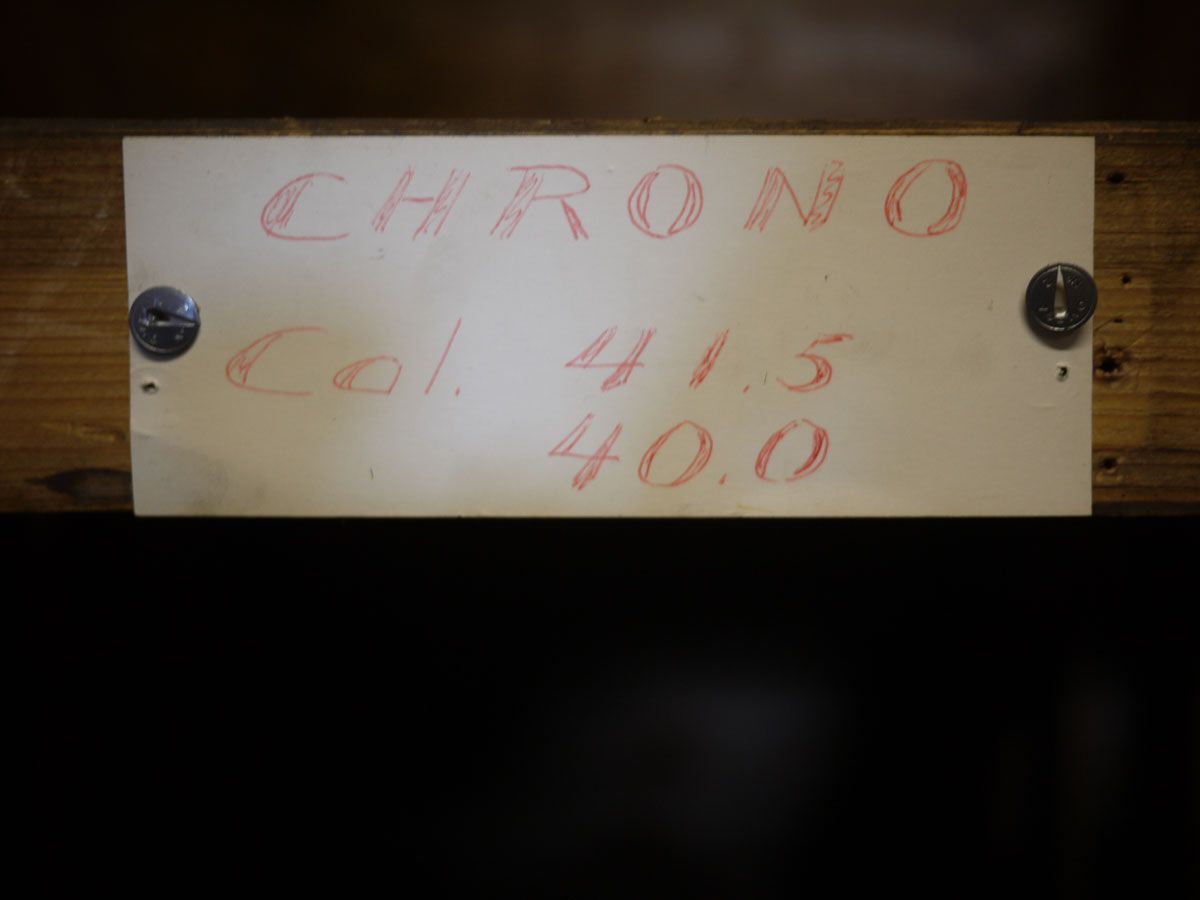

When I looked down, I could see the label identifying what had been there

This is the Zenith internal code for the El Primero chronograph movement, and this small wooden space, tucked up in the eaves of a Victorian factory attic was where Charles Vermot had secreted them and where they had lain, safe from prying eyes, for almost a decade.

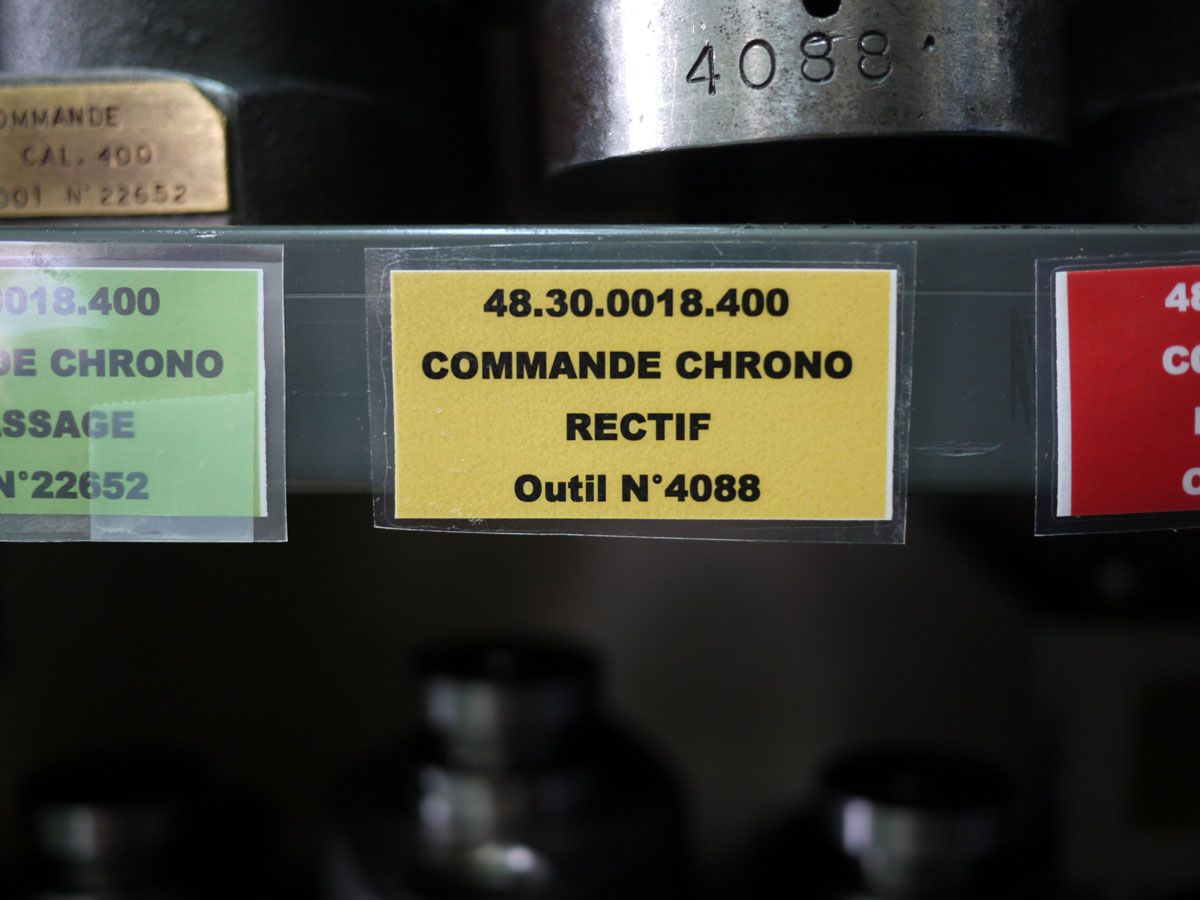

Here they are, back in use, and now on rather more sturdy metal shelves down in the factory.

The watch shown at the start of this piece is the limited edition El Primero chronograph that Zenith launched last year in honour of Charles Vermot, and this year they will launch a total of three watches named after the man who saved the patrimony of the company.

These are really some amazing pictures and an important part of watchmaking history. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteIf you have not heard about the The Goldgena Watch Project, I recommend that you check it out, as it also has an interesting watchmaking project going on right now.

Get the latest watch news from around the world—new releases, brand updates, trends, and expert insights. Stay informed with everything happening in the watch industry.

ReplyDelete