The last year or so has been a period of retrenchment for the Swiss watch industry, other than in one area; more watch company heads have departed during this period than I can count. And many of them were not just your basic managers, they were iconic heads, closely identified with the brands they ran, folks like Manuel Emch from Jaquet Droz and Frank Muller from Glashutte Original; but, perhaps no watch company head was as closely identified with his brand than Thierry Nataf from Zenith, and with his recent departure it is time to look at the company he has left and to think about its future (with a sideways look at its history).

If you had to describe Thierry Nataf in one word, it would be ‘flamboyant’ and flamboyant was the direction the watches also followed, Zenith were one of the first companies to open their dials to show the workings beneath, the cases became larger culminating in the XXT line which topped out at 45mm and, in the iconic El Primero line, huge Franck Muller like distorted numerals adorned some of the dials. If there is one common thread between all of the above, it is that they are about the look of the watch & not the movement and the truth is that Zenith has always been about the movements, going all the way back to its birth in 1865. The firm has an almost forgotten history as one of the leading companies in the Swiss chronometer competitions. Until the competitions ceased in the 1960s, Zenith always ‘punched well above its weight’ regularly beating the likes of Omega, Rolex & Patek Philippe to claim the gold medal.

It was with this history, ancient & modern, in my mind that I sat down recently with Jean-Frédéric Dufour, the newly appointed CEO & President of Zenith at Baselworld. We had two meetings, which amounted to almost an hour, in the company’s stand, and whilst waiting for our meeting to start it was interesting to note that the cabinets inside the stand displayed not the current models, but rather the watches from the firm’s recent history, the 1950s to the 1980s.

M. Dufour came to Zenith from Chopard, where he was the head of product development, prior to Chopard he had spent time at Ulysse Nardin & with the Swatch Group. In other words, he is a watch guy through & through, unlike M. Nataf, whose previous employment had been within LVMH’s champagne operations.

Ever the diplomat, M. Dufour declined to comment on his predecessor but his very different vision was encapsulated in the statement he made to me, “We plan to make classically beautiful watches between 40mm and 42mm”.

His first job at Zenith was the distasteful one of declaring almost a third of the workforce redundant, shortly after he took an even sharper axe to the model range. He pared the 800 models in the 2009 catalogue to a much more manageable 150 and slowly introduced new models all based on historic models from the collection and one significant new model, the El Primero 1/10th second Striking Chronograph.

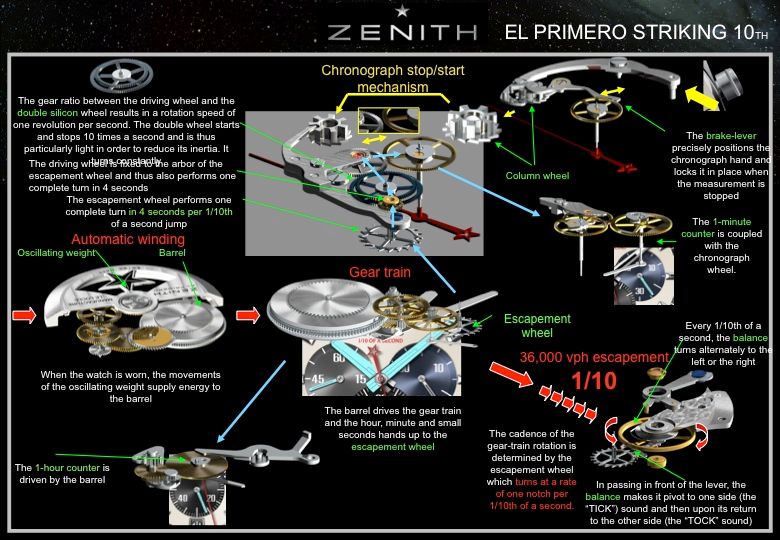

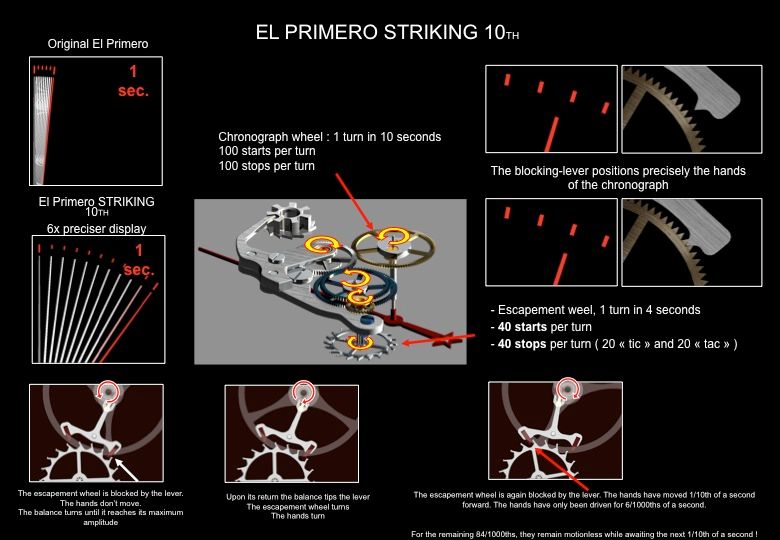

Looking just like one of their watches from the 1970s, until you look much more closely and see that the date aperture has moved from the traditional 4:30 position to the bottom of the dial and then you notice the inner bezel marked from 1 to 10 with each division in turn divided into tenths. As is well known, the El Primero beats 36,000 times an hour, this can otherwise expressed as 10 times each second and it is this ability to ‘chop’ each second into ten individual units that the new model demonstrates. The red sweep centre hand (proudly bearing the Zenith star as its counterweight) makes a complete sweep of the dial every ten seconds. But much more than that, it stops dead on each one tenth of each seconds mark on the bezel. Thereby ‘striking’ each tenth of a second and it is from this ability that its name derives.

The technology needed to accomplish this feat is simultaneously simple and complex, essentially there is second escapement which stops and starts the sweep hand ten times each second. Careful study of these diagrams (supplied by Zenith) will probably explain it better than I can. The first is an explanation of the ‘basic’ chronograph, whilst the second explains the striking mechanism in detail.

The key to this new functionality is the chronograph stop function. When the chronograph is stopped, the hand-locking system brings the hand to an extremely precise halt, since the brake-lever positions the hand between two of the 100 teeth on the chronograph wheel, thereby further enhancing the precision of the 1/10th of a second read-off.

The original El Primero movement sweeps around the dial in 60 seconds in tiny 1/10th of a second jumps, meaning the chronograph hand performs 600 jumps a minute. In this new jumping seconds model, the ultra- fast stopping and restarting of this large chronograph hand 10 times a second calls for a greater amount of energy. The watch functions had to be significantly improved and optimised to enable this energy- consuming acceleration. Seeking to reduce the energy required naturally entailed making the movement wheels as light as possible, which is why the double wheel at the heart of the system is in silicon – a material three and a half times lighter than its traditional counterparts.

The watch is available in either steel or rose gold in a 42mm case and will be launched in the UK in April at a price of £7,300 including VAT.

The El Primero movement is the core of the product line for Zenith and from 1988 until 2000 when they were selling movements to Rolex for the Daytona; it is safe to say that the El Primero saved Zenith. But what is not so well known is that the El Primero itself once needed saving.

The tale goes back to 1975 when the US firm, Zenith Radio Corporation, owned Zenith; the quartz revolution was at its height and mechanical watches were in the doldrums. The owners decided that mechanical watches had had their day & the future belonged to electronic watches. Thus, an order came down from the US HQ to dispose of all the tooling for the movements & to sell the tools as scrap. Despite protests from management & watchmakers, the decision was irrevocable and furthermore the Swiss staff was ordered to dispose of the plans & blueprints, as these would also be of no use in the brave new electronic world. However Zenith has another tradition, people stay there for a long time; several of their current employees have been with the firm for over a half-century. This comes about through one thing; loyalty and it was this loyalty to the firm & its history & tradition that saved the El Primero. Charles Vermot was a senior watchmaker with the company & was entrusted with the disagreeable task of disposing of the El Primero tooling. Rather than follow orders, he meticulously wrapped each item, labeled it & took it home where the tools were arranged on shelves in his attic. And, in a notebook he copied down the exact procedures necessary for making the movement from scratch using the tooling he had saved.

And, it was in the attic that the history of the El Primero might have stayed if it hadn’t been for another small company in the neighbouring town of La Chaux de Fonds, who asked if Zenith might have some El Primero movements for sale. The resulting watch, the Ebel 1911 chronograph launched in 1982 proved to be a huge success for both firms, and so the tooling was recovered, put into use and before long Swiss watch companies were beating a path to Zenith’s door clamouring to use the only high quality automatic chronograph movement then available. The El Primero is a remarkably efficient movement, bearing in mind its 40-year-old design, it runs for 50 hours at full wind but if the chronograph is running, that autonomy is only reduced by 5 hours. However it is important to realize that the El Primero was designed in the 1960s when craftsmanship was at its height and it was not designed for large-scale industrial production, unlike (for example) the Valjoux 7750.

In fact during its 41-year history (including the enforced exile in Charles Vermot’s attic) the total of all El Primero movements ever made (including the hundreds of thousands found in the Rolex Daytona 16520) add up to only 600,000, by contrast over 1,000,000 Valjoux 7750 movements are made each year.

It is with this history in mind that one of M. Dufour’s first orders was to commission a version of the El Primero chronograph in memory of Charles Vermot, made in an edition of 1,750 watches (to commemorate the year he secreted the parts away) the 42mm steel watch has a blue dial and will be available this summer at a price of £6,000 including VAT.

The other famous movement is the company’s history is the manual wind cal 135, the one that won all those chronometer competitions in the 1950s, they still have a few of the original movements in their inventory & there are plans to case a few of them in an exclusive edition for collectors. It is significant that one of M. Dufour’s first public engagements was at a ceremony to honour Ephreem Jobin, the 100 year old watchmaker who designed the cal 135 movement just after the second World War.

M. Dufour is seen here presenting M. Jobin with one of the commorative watches whilst he holds one of his originals, at their feet are his original drawings for the movement.

The Zenith press release announcing the creation of a watch to celebrate this achievement is here.

Like all Zenith movements, the Calibre 135 stemmed from the company’s determination to create ever more accurate and reliable movements – a tradition cultivated since its founding in 1865, illustrated early on by its remarkably accurate pocket-watches, and accentuated by the emergence of wristwatches.

Introduced in 1948 at the height of the fiercely-fought race for precision between various watchmakers, the Calibre 135 comprised several innovative and sophisticated technical features that enabled it to win numerous prestigious Neuchâtel Observatory chronometry prizes, including five years in a row from 1950-1954 – a record in itself. Its total tally of such recognitions comprised around 200 individual honours, two-thirds of which were first prizes, as well as five for series- honours.

Ephrem Jobin, born in 1909 and doubtless the world’s oldest living watchmaker, played a variety of roles in the development of Zenith at this strategic time. During the period he spent at Zenith between 1939 and 1954, he was responsible for developing three complete calibres, including the legendary Calibre 135.

He quickly grasped the importance of reorganising manufacturing procedures based on a truly global vision of production. When commissioned in 1946 to invent “a 30 mm calibre” capable of meeting the norms of the Neuchâtel Observatory competition, he set about conceiving and developing it according to a set of standards designed to enable it to achieve the best possible chronometric performances. He single-handedly supervised the entire project.

Ephrem Jobin’s recipe for success with the Calibre 135 included using a large barrel to increase power reserve, as well as an oversized balance which, as part of the regulating organ, plays a crucial role in enhancing precision. This approach called for a complete rethinking of the movement design, including offsetting the minute wheel from the central axis so as to provide space for the enlarged balance. The observatory competition version of this legendary movement (Calibre 135.0) was equipped with a Breguet overcoil balance-spring, as well as a single or double arrow-shaped index or regulator ensuring balanced friction and enabling optimal adjustment.

Seen above is one of the gold medal winning cal 135 movements in its wooden testing box, the shape of the box allowed it to be easily placed flat in any of the 6 positions needed for the test.

Moreover, in addition to its outstanding chronometric feats, Calibre 135 was also adapted to produce commercialised versions, all of them chronometer-certified and sold with a rating certificate. They were equipped with an off-centred disc regulator and adorned with Côtes de Genève.

The chronometer-worthy precision of Calibre 135 entailed a naturally limited production volume reserved exclusively for high-end watches. 11,000 of these movements were produced, meaning that watches housing this calibre remain a much-coveted item among connoisseurs and collectors. The specialised press described it at the time as “one of the best wristwatch movement in watchmaking history” – a title it undoubtedly still deserves thanks to its superlative performances and surprising modern construction. This refined aesthetic appeal, accentuated by the classic design and the meticulous finishing of this calibre, vividly evokes the pure, restrained classicism of Zenith watches.

This historical retrospective tribute to Calibre 135 thereby honours an exceptional example of horological know-how, vividly embodied in the person of an archetypal master-watchmaker and distinguished centenarian, Ephrem Jobin.

Zenith has indeed decided to commemorate this jubilee by issuing a special 100-piece limited- edition watch in his honour and presenting him with the N° 100 model in a nod to his milestone birthday. It is powered by a self-winding COSC-certified Elite 689 movement having notably benefited from the technical progress made during Mr. Jobin’s time at Zenith.

The 18-carat rose gold case with sapphire crystals on either side frames an understated, elegant brown sunray dial graced by 18-carat rose gold faceted hands and hand-mounted applied hour- markers. Teamed with a hand-crafted brown crocodile leather strap lined with silky Alvazel calfskin and fitted with an 18-carat rose gold pin buckle, this handsome model eloquently conveys Zenith’s gratitude to Mr. Jobin for his major contribution to the history and development of the brand.

It was interesting to see that in the cabinets inside the Baselworld Zenith stand were several divers’ watches from the 1950s and 60s, even though the company does not currently have a true diver’s watch in the catalogue, when questioned about this M. Dufour responded “Divers’ watches are part of our history and will be part of our future”.

He also confirmed that movements will not be sold to companies outside the LVMH ‘family’ (Tag Heuer/Dior/Louis Vuitton) and that all Zenith watches will only be powered by Zenith movements.

During both our meetings M. Dufour was constantly interrupted by assistants asking for his presence elsewhere, it is to his credit that he remained focused on our meetings and the level of activity on the stand assured me that the continued future of the brand is safe and that it is even safer in his hands.

No comments:

Post a Comment